Share:

How can rewilding help restore ecosystems globally?

Did you miss the first rewilding webinar organised by the Rewilding Community of Practice back in July? Our first event revolved around the question “What is Rewilding?” Below we will share our speakers’ personal rewilding stories.

Learn more about the work of Erik de Boer on Mauritius, James Meadows in Spain and Purnima Devi Barman in India and find out what rewilding means to them.

Paleoecological insights into rewilding – Tales from Mauritius

Erik is a paleoecologist affiliated with the University of Barcelona and the University of Salamanca. He is using long-term data of species responses to environmental change to study species survival mechanisms and predict future changes in biodiversity. He specifically focuses on the impact of human arrival on the landscape and the consequences of extinction in island ecosystems.

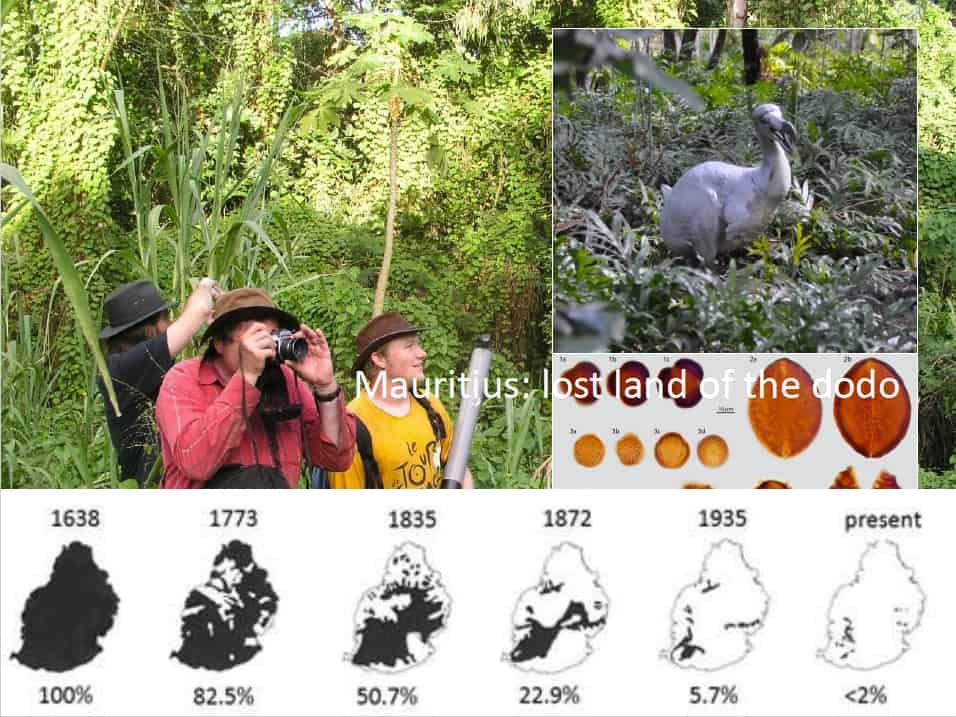

Erik discussed his research over the last 10 years on the Indian Ocean Island of Mauritius, once home to the illustrious Dodo bird. He shared his experiences of working and collaborating with local ecologists, rewilding organizations, sugar cane companies and Mauritian students as the next generation of biodiversity conservationists.

During his presentation we took an introductory look at how paleoecological research can guide rewilding initiatives. Paleoecological records can be seen as time-machines to investigate how landscapes and its ecosystems have changed over time. This provides insights into the natural baseline dynamics of ecosystems under the influence of climate change, internal processes of plant-animal interactions, and human impact.

“Islands are usually colonized by humans relatively late in history. Therefore, we can study natural dynamics before humans set foot in these remote areas and record the ecological consequences of species and habitat loss following their arrival.”

Paleoecological research on the island of Mauritius (Indian Ocean) shows that the island has been completely changed in less than four centuries of human occupation; the extinction of the famous dodo provides only one facet of biodiversity decline.

Despite the ecological crises happening on Mauritius, the island hosts a variety of progressive conservation projects to restore lost ecosystem processes and develop resilient biodiversity. These projects – including native tree nurseries and giant tortoise reintroductions – bring together scientists, local organizations, conservationists, and landowners, and activate local students as the next generation of biodiversity conservationists.

“Rewilding for me is all about a collaborative and progressive effort towards a sustainable future.“

— Erik de Boer, Paleoecologist

Co-existing with nature and developing integrated solutions

James Meadows is in his final year of his bachelor’s program studying International Development Management, having specialised in Rural Development and Innovation at Van Hall Larenstein University. His thesis for Wageningen Economic Research Institute focuses on exploring contributory socio-economic factors that influence household food security and vulnerability among women in Kibera, Kenya. Over the past 4 years he has been working on participatory projects inside and outside of university inrural development projects tackling challenges such as shrinkage, rural to urban migration and exploring ecotourism opportunities for rural communities.

James’ presentation was about co-existing with nature and discussed some tools, cases and participatory approaches to develop integrated solutions so that we can learn to live in nature rather than around it.

James pointed to the importance of recognising, becoming aware and connecting to our landscapes, wherever that may be. He discussed the importance of collaboration and using and developing Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships (MSPs). An MSP approach uses creative methods and tools to initiate collective action that can develop new sustainable solutions to local challenges and development opportunities.

“For all the benefits rewilding can provide, individually recognising and understanding the ecological, biological and socio-cultural values in our landscapes is crucial to adopting new methods to restore and look after our natural environment.”

James presented data that showed human impact on biodiversity and the changes it created in ecosystems. In order to restore biodiversity and support the regeneration of such systems, new Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships and tools are needed to to connect and align local stakeholders and landscapes.

“Rewilding for me is more than supporting an endangered animal species, but finding new ways to connect people to their own landscapes so that problems such as supporting an endangered species can be looked after and cared for by the people who live alongside it..”

— James Meadows, Rural Development and Innovation Specialist

Establishing a people’s movement to save an endangered species in Assam, India

Dr. Purnima Devi Barman, globally known as “Stork Sister” and locally as “Hargila baido”, is a conservation biologist associated with Aaranyak, a conservation NGO in Assam, India. Apart from conducting research on the endangered Greater Adjutant stork (Hargila) in the past 15 years, she is a founder of an all rural women army group called “Hargila army”, comprising of 10,000 female members and 400 forefront active leaders in villages in Assam. She is the recipient of the Whitley Award 2017/Green Oscar 2017, the UNDP India biodiversity Award 2016, and the Earth Hero Award by the Royal Bank of Scotland. She has been conferred with Nari Shakti Purashkar by the President of India which is the highest civilian award for Indian women. Purnima has a diploma in environmental education and has done her Ph.D at Gauhati University in Assam on the topic Foraging ecology, breeding success and genetic status of endangered Greater Adjutant Stork (Leptoptilos dubius) in Assam, India.

Purnima presented her story of a female led community conservation movement in Assam is saving the endangered Greater Adjutant stork (Hargila) by changing local perceptions, linking the bird to Assamese traditions and rituals, and empowering 10,000 women currently known as the “Hargila army” in Assam, India. This conservation model could be replicated by many community driven projects in the world to connect people and nature.

Purnima’s presentation highlighted the power of local people/communities and especially women community members towards changing the fate of an endangered species from a bad omen to a sacred species.

From children to nest tree owners, all stakeholders were involved in various activities towards the conservation of this bird. The feeling of ownership of the nesting trees became a pride factor among the communities soon after. An all-women “Hargila army” (protector of storks) comprising of 10,000 rural women was created in the village to lead the conservation initiatives. Nest tree owners and the Hargila army members were provided with alternative livelihood options so that they wouldn’t cut the trees for livelihood support.

Now, after more than 10 years, we can see excellent results. Nest numbers have increased from 26 in 2006 to 221 in 2020. Not a single nesting tree has been cut in the last ten years in the Kamrup district. The nesting colony of Dadara-pacharia-Singimari village complex of Kamrup district harbours more than 60% of its global population and has become the biggest nesting colony of this bird.

“Rewilding to me means coexistence of people and biodiversity. We must build the leadership of our communities as fore front leaders and include more rural women in our decision making to achieve sustainable conservation goals “

— Dr. Purnima Devi Barman, Conservation Biologist

Learn more about the Rewilding Community of Practice, what we do and how you can join us at the GLFx platform of the Global Landscape Forum.